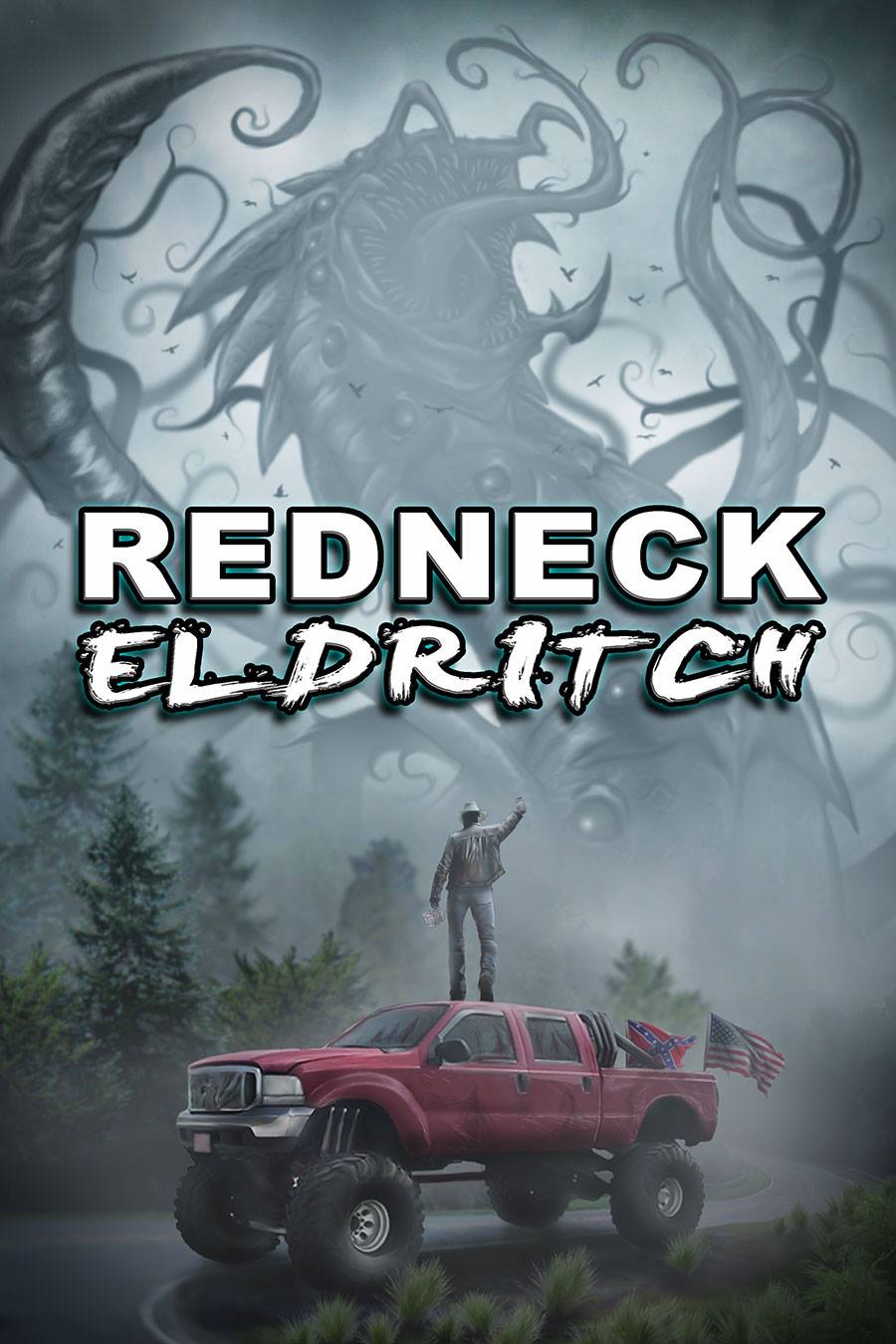

REDNECK ELDRITCH Sneak Peek: “Recording Devices” by D.J. Butler

The old man’s gnarled right hand stopped, springing into the air above the trembling banjo strings and freezing in clawhammer shape, index ever so slightly extended and thumb to the square.

The old man’s gnarled right hand stopped, springing into the air above the trembling banjo strings and freezing in clawhammer shape, index ever so slightly extended and thumb to the square.

The short sustain of the banjo meant the strings sang their final chord with power, but briefly, and then fell still and silent.

John Hanks reached over to stop the recorder and set the microphone down. He leaned back on the three-legged stool next to the open trunk of the 1937 Ford that held the bulky recording device and wiped sweat off his forehead.

The musician’s name was Roscoe, wasn’t it? Suddenly he wasn’t sure. He’d recorded the songs and playing of so many of these hill folk that their faces and names were starting to fuse, Earl and Sunny and Andy and Roscoe. John’s eyes and ears itched, and he rubbed them.

“Thank you, sir.” He’d just avoid the name entirely, it wasn’t worth wasting any time on it. “You sure that’s the last one you know?”

The old man’s head swiveled on his neck. His jaundiced eyes, punctuated with glittering dark irises, pierced through the trees surrounding his dog trot cabin and seemed to search out the entire knob of rock that in this part of the world passed for a “mountain.”

“Waall…” The banjo player popped his neck by cranking his head in a circle and licked his lips. “Not all songs is proper to sing. Not in public. And some songs just en’t proper at all.”

John restrained a sigh. Instead, he dug into the cash in his waistcoat pocket and pulled out thirty-five cents. “There you are, Roscoe,” he said. “Seven songs and tunes I haven’t heard before, a nickel apiece.”

“Name’s Earl.” The banjo player looked down at the dull change in the palm of his hand: two dimes, three nickels, ten pennies. “I got another, I reckon. It’s gettin’ dark, though.”

John patted the microphone. “The folks hearing the recording will see you just as well in the darkness as in broad daylight,” he cracked wise. “And if you’re worried about me getting back down the… mountain,” he swallowed the word in one bite, “the car’s got headlamps.”

“It en’t that. It’s only… iffen.” Roscoe licked his lips again. No, Earl. “I need the money. Nickel goes a long way these days.”

[pullquote align=”left” cite=”” link=”” color=”” class=”” size=””]“Not all songs is proper to sing. Not in public. And some songs just en’t proper at all.”[/pullquote]

John let him think about it. Some of these old folks up in the hills couldn’t wait to get someone to listen to their treasure trove of nursery rhymes, blues, ballads, and hymns. Others acted like they were sharing the most precious thing in the world, and had to be bribed, coaxed, reassured, and sometimes even tricked.

“You jest gonna record it on that… what’d you call it?”

John nodded and grinned. “It’s a mobile recording device.” The recorder was a chunky machine that ran off the Ford’s battery and turned sound waves into grooves in a wax cylinder by way of a handheld microphone. It was state of the art, or at least as state of the art as you could reasonably be expected to drag up into the hollers of Appalachia.

“It en’t dark yet,” Earl decided. “You hold a red an’ a white thread side by side, an’ iffen you can’t tell the difference, it’s dark. En’t that what them old presters used to do? Let’s git this one down, an’ fast.” He leaned over his banjo to whisper to John, and his voice dropped an octave. “An’ I en’t singin’ the words, not to this song, nuh-uh. But I’ll play you the tune, an’ I wager you en’t heard it. That worth a nickel?”

“Has it got a name?” John turned on the recorder and held the microphone up to Earl. Still plenty of juice in the battery, he was sure—he had no desire to spend the night in Earl’s dog trot.

“No, it en’t.” Earl squinted. He must know, from all the tunes he’d already recorded that afternoon, that John wanted some kind of label, a way to catalog any piece of music. “But it’s a tune as old as the hills.” As he said it, he was adjusting the tuning on the banjo. At first, John thought it was just tuning up, but then he saw and heard Earl drop the second string an unnatural amount, and when the wiry farmer ticked the strings off one after the other with his fingernail, the resulting chord sounded… off. Modal, but beyond modal. Microflatted. Intervals all wrong. Unearthly. “Old as the hills,” the old man repeated.

“Let’s hear it.”

Earl played.

True to his word, he didn’t sing. His tune was long and discordant, a double drone that must have been some sort of diminished fifth by way of interval, or maybe a diminished sixth, but it seemed to John that the distance between the drone notes grew and shrank as the sound moved through time. The drone was accented by choppy bits of melody on the first, third, and fourth strings, shreds of sound that seemed to John like voices.

Not human voices. And not singing.

Old Earl’s drone felt like the thrum of earth moving through infinite time in mist and darkness, and as John’s eyes seemed to fill with those mists, he would have sworn he saw standing stones jutting from the mists, and heard voices shrieking in joyous celebration. Only the voices weren’t human—they sounded more like birds, but not any bird he’d ever heard sing before.

John wanted to rub the hallucination away from his face, but he had to hold his position very carefully or he would fail to capture the sound on the recorder. His eyes and ears itched and his legs felt asleep. Too much time sitting on this stool.

The banjo shrieked again, or was it a bird? Or was it Earl?

Or was it John?

The tune stopped, abruptly.

Darkness had fallen. Darkness as Earl himself defined it; John could no longer tell the white stripes from the red in Earl’s old cotton shirt.

“The nickel,” Earl said.

John fumbled for the coin in the darkness. “You say there are words?”

“I won’t sing ’em. En’t no place safe to sing ’em except mebbe in church on Christmas, an’ then I reckon it’d be spittin’ in Jesus’ eye.”

John found himself curious. No, not curious. He found himself craving. He had a strong and unexpected desire to know what words went with that strange, shuddering, atonal tune.

And publish them.

“What about written down?” he asked. “Would you write them? Or do you know where I could find them written?”

Earl was so still that for a moment, in the darkness, he was invisible. When he shook his head it was in a shudder, a sudden paroxysm of motion that almost knocked John backward. “I cain’t.”

“Or won’t?”

“Difference don’t matter.” Earl stood slowly. His banjo was a light one, an old Sears Roebuck model with an open-back pot, but the slow hunch in which he rose suggested a heavy burden on Earl’s shoulder.

Arthritis, John told himself. Bad nutrition. Inbreeding, maybe.

“’Cept mebbe one person,” Earl said. It was an afterthought, spoken from the dark shadow of the dog trot running between the two cabins of Earl’s house. “Up top of the mountain. Name’s Hodder. He’s got books, an’ I reckon he might have the words written down somewheres.”

“‘Hodder.’ Is that his first name, or his last?”

“All the name he has. He ain’t got a clan, not like most folks.”

“What do I ask him for? I can’t just say ‘the song as old as the hills,’ can I?”

“The call,” Earl said slowly. He had disappeared entirely into one of his cabins, and John couldn’t even tell which. “Just tell him you want to know the words of the call…”

**********

This is just one of the stories in the anthology Redneck Eldritch, coming in April from Cold Fusion Media!